Rishad Tobaccowala: Workplace as Community

In her book Retirement and Its Discontents, Michelle Pannor Silver’s research reveals that for millions of people work is much more than output or income they generate. It is a source of meaning and social identity. It is where they feel intellectually stimulated and can express their creative selves. It is where they feel a sense of community and connection.

If organizations lose these attributes, they will struggle to attract and retain the best talent. Admittedly, this is a challenge when they feel in a mad competitive scramble and think that only by devoting all their time and money to data, measurement, and the like can they survive. At the same time, they need to find a middle ground, a place where they make room for story, for meaning and identity. If they lose these crucial elements, what does it matter that they can measure stuff in nanos?

The Importance of Community at Work.

People are looking for work to provide a sense of community as never before. In a Harvard Business Review article, Lori Goler and her colleagues identified three factors as necessary for job satisfaction: career, community, and cause.

“Community is about people; feeling respected, cared about and recognized by others. It drives our sense of connection and belongingness.”

You might think that community is only important to certain types of people holding certain types of jobs in certain countries. Goler, however, found that community (as well as the two other factors) transcend types. In fact, on a 5.0 scale, engineers rated the importance of community as 4.18—a surprisingly high rating from a group that is often thought of as idiosyncratic loners.

Think about community as a forum for storytelling in the broadest definition of that term. In any organization where people have a strong sense of community, they also are constantly telling and listening to stories—stories about the behavior of bosses, about the machinations of teams, about the heroic efforts of one leader and the villainous actions of another. More than that, stories about the organization reside in all employees’ heads.

A major merger with a competitor a few years ago is analogous to a historical treaty signing between formerly warring nations—this event and everything that led up to it is embedded in people’s consciousness.

The multiple stories of an organizational community provide people with common language, ideas, and personalities, offering a narrative of which they are a part. As Goler asserts, community fosters a sense of “connection and belongingness,” and these positive attributes emanate from the ongoing organizational story.

The Loss of Deep Engagement.

Companies used to talk about their people as family. In the wake of downsizing and in workplaces where people work remotely, travel constantly, and change jobs frequently, family no longer seems an appropriate term. But should workplaces be the opposite of family—impersonal environments where people measure their satisfaction by the size of their paycheck and bonus?

To address this question, let’s start with the highly influential paper “Measuring Meaningful Work,” which examines several studies and concludes that this type of work is aligned with passion and seen as a higher calling; growth in a job and making a difference in the world represents a greater purpose than income.

Similarly, CEO Tony Schwartz identifies twelve attributes of a great workplace and notes that a key to these attributes is standing “for something beyond simply increasing profits. Create products or provide services or serve causes that clearly add value in the world, making it possible for employees to derive a sense of meaning from their work, and to feel good about the companies for which they work.”

Most organizational leaders probably agree with these notions of meaningful work, at least in the abstract. Yet, many don’t create the necessary conditions. Willis Towers Watson, a global advisory firm, found that two out of three workers were not fully engaged at work, with almost one-fifth completely disengaged.

“The most significant factors relate to how their supervisors support them on the job, their levels of stress and the severity of their workloads. For the detached, by contrast, company leadership stood as the focal point. Detached workers lack an emotional connection to the organization, stemming from feelings that they do not work for a company with strong values, clear vision, and a leadership team that takes employees’ interests and needs into account”

Architecting Emotional and Physical Landscapes.

Organizations possess a lot of physically and emotionally detached workers these days. Think of it from a landscape perspective. There’s the physical landscape of homes, offices, off-site meeting spaces, and so on.

There’s also the emotional landscape of relationships with bosses and fellow employees.People feel spaces and connections both emotionally and physically, and therefore sculpting environments is key for establishing meaning and purpose. These spaces, whether they be emotional or physical (whether it be an office, an event or an off-site), are where the culture of a company is created and sustained.

In these spaces, stories are told; stories about values as they relate to customers, employees, communities, and shareholders. Stories about the company’s founders, how it was founded, and why it exists beyond creating products and services. Stories that employees create as they find purpose and growth and meaning.

These stories are lost, or at least diminished, when people fail to get together in-person on a regular basis or fail to feel emotionally safe to speak up and share stories. When they’re enmeshed in data, working remotely, transfixed by screens and not fully present for other reasons, people don’t tell or hear the stories that imbue the workplace with meaning.

Companies will need to combine working from home, the office, events and experiences in different ways for differently experienced people and jobs to balance the benefits of distributed and in-person interaction. They will not be a single model for every firm or level and in the differences will be the challenge and where the magic of managing will lie.

Robots Compute. People Dream.

At a time when people change jobs with almost the same regularity with which they change their passwords, community keeps people loyal to their organizations. More than that, in a volatile, uncertain world of work, it provides certainty and satisfaction. We need to be aware that in our rush toward all things digital, we’re endangering this sense of community.

In author Don DeLillo’s landmark novel Underworld, he writes:

I was driving a Lexus through a rustling wind. This is a car assembled in a work area that’s completely free of human presence. Not a spot of mortal sweat, except, okay, for the guys who drive the product out of the plant—allow a little moisture when they grip the wheel. The system flows forever onward, automated to priestly nuance, every gliding movement back-referenced for prime performance. Hollow bodies coming in endless sequence. There’s nobody on the line with caffeine nerves or a history of clinical depression. Just the eerie weave of chromium alloys carried in interlocking arcs, block iron and asphalt sheeting, soaring ornaments of coachwork fitted and merged. Robots tightening bolts, programmed drudges that do not dream of family dead.

This paragraph has stayed with me for a long time, particularly these three lines:

Hollow bodies coming in endless sequence.

There’s nobody on the line with caffeine nerves or a history of clinical depression.

Robots tightening bolts, programmed drudges that do not dream of family dead.

All industries are becoming increasingly automated. While DeLillo’s book described robots in an auto plant, we now see robots of some type nearly everywhere.

With the dawning of AI, the rise of intelligent objects with the Internet of Things, and new interfaces such as voice, A/R and V/R we will see our workplaces augmented, encrusted, and infested with machines of every type.

In today’s distributed workplace, where we interact across screens with machines that spew data that is collated and compiled by computers, how do we maintain a sense of community?

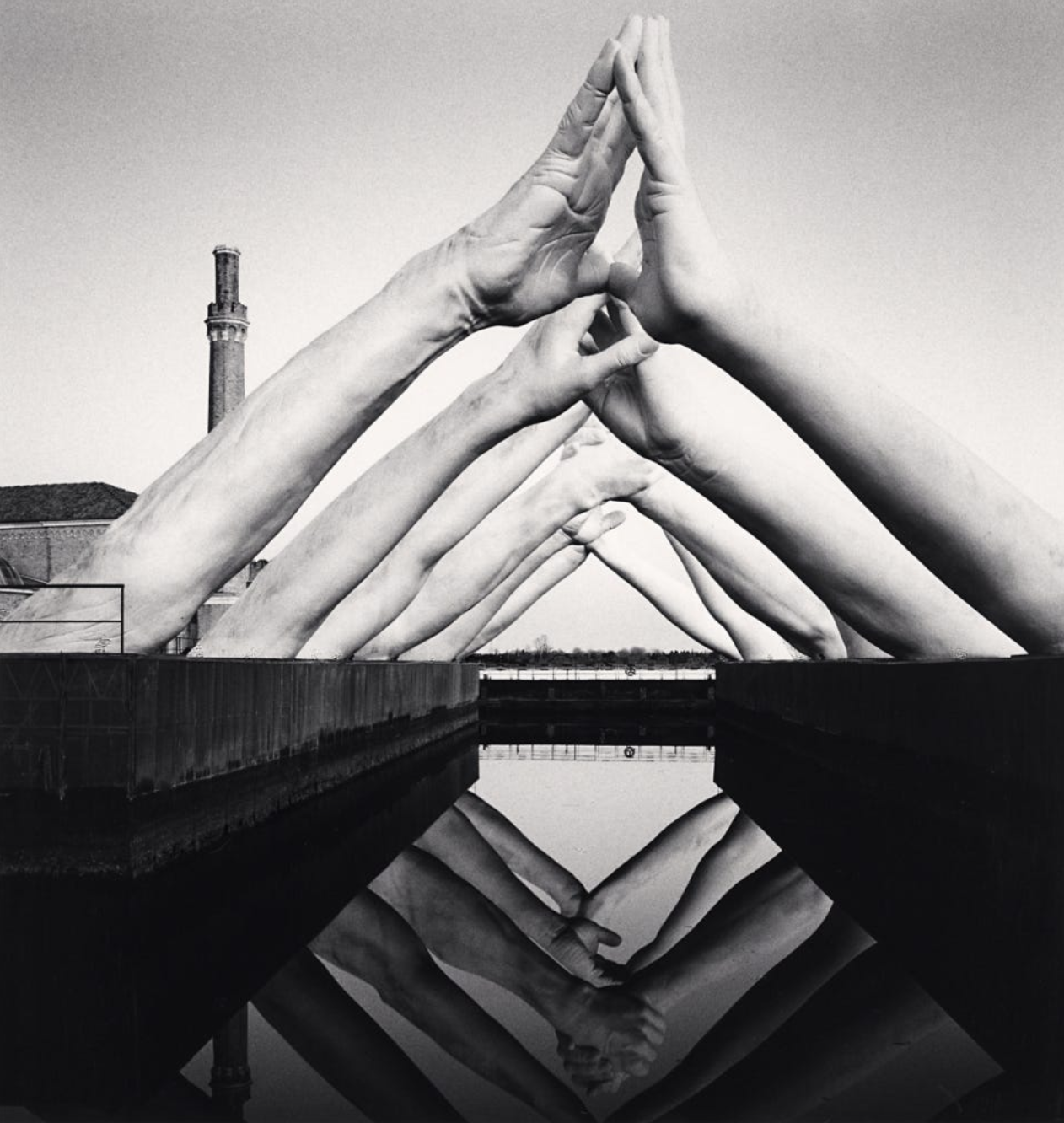

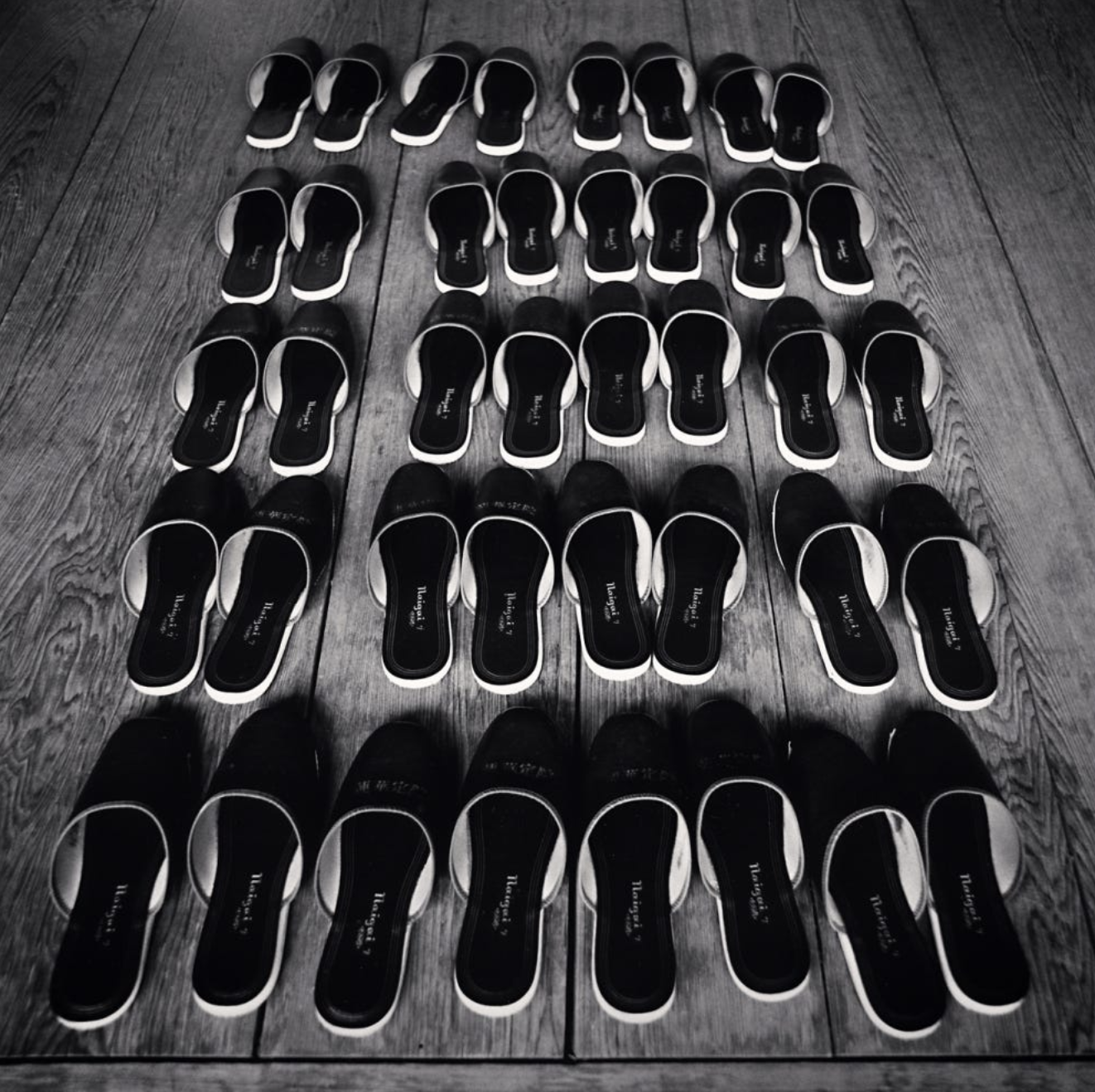

Photography by Michael Kenna.